A days-to-shell build

A builder wants a garden room shell in days (even one day for a small structure), a self-builder wants confidence in every decision, and a turnkey client wants minimal disruption. A conventional timber frame can spend that same window just on framing and insulation. This is the moment SIPs were built for: pre-insulated structural panels that assemble fast, seal tight, and keep heat where it belongs, with support from teams who know the UK market.

From timber framing to SIPs

Traditional timber framing is familiar, but it fights physics. Studs interrupt insulation, joints leak air, and thermal bridges drag down performance. SIPs replace the repetitive stud lattice with continuous insulation and a structural skin, so you get speed without sacrificing strength.

Comparison

Timber framing enclosures compared

The timber framing community adopted SIPs because they enclosed frames faster and added performance.

Timber frame + conventional infill

Multiple layers to assemble

- Insulation and structure are separate tasks

- More joints to seal, more thermal bridging

- Slower to achieve a weather-tight shell

Timber frame + SIPs

Single panel enclosure

- Structure and insulation installed together

- Adds stiffness and airtightness to the frame

- Faster enclosure with fewer gaps

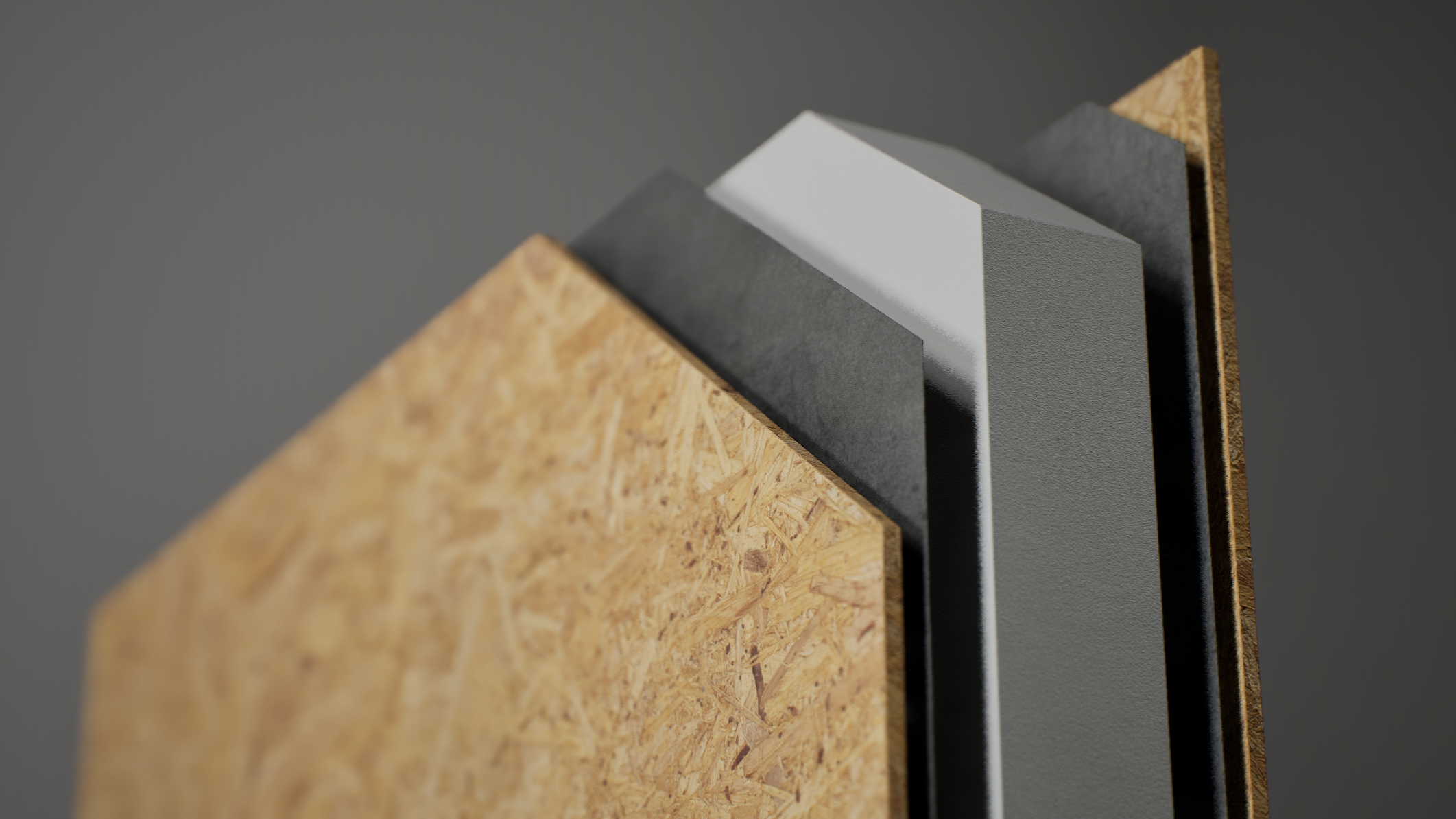

What a SIP actually is

A Structural Insulated Panel is a sandwich that carries load. Two structural facings (usually OSB) are bonded to an insulating core (EPS, PIR, or PU). The glue bond makes the assembly behave as a single structural element.

Key parts to know:

- Skins (OSB): take tension and compression like an I-beam flange, and provide racking resistance.

- Core (EPS, PIR, or PU): handles shear and keeps the skins aligned.

- Bond line: the hidden hero that makes the composite action possible.

Why SIPs became mainstream

SIPs were developed in the 1930s, but they grew as building codes demanded more energy performance. In the UK, tighter Part L targets and airtightness testing pushed designers toward continuous insulation and fewer joints.

The green revolution effect

Energy efficiency, airtightness testing, and carbon reduction targets pushed builders toward systems that could be both structural and insulating. SIPs became a practical way to meet lower U-values without building excessively thick walls.

The role of SIPA

The Structural Insulated Panel Association (SIPA) and its members drive standard details, training, and testing. SIPA news and technical updates are worth monitoring because they reflect changes in best practice, fire testing, and evolving system details.

Where SIPs are used

- Floors: long clear spans with fewer joists.

- Walls: simple, fast shell erection with minimal thermal bridging.

- Roofs: vaulted interiors without trusses.

Inside the factory

The manufacturing sequence matters because it dictates quality:

- Sheets are cut to size and prepped.

- Core insulation is cut or injected.

- Adhesive is applied to the skins.

- The stack is pressed under controlled pressure.

- Panels are trimmed, labeled, and packed.

Batch injection vs cut core

Some manufacturers batch inject foam into a mold between skins, while others cut core boards and bond them. The end goal is the same: a uniform bond line and consistent density. Ask how panels are made so you understand tolerances and lead times.

Core materials in plain English

- EPS: cost effective, stable, easy to source.

- PIR: high insulation performance with better fire characteristics; widely used in the UK.

- PU: high insulation per thickness, often used in specialist panels.

- XPS: occasionally used, but less common in SIP manufacturing. UltraSIPS commonly supplies EPS and PIR options in the UK, with specification guidance based on the project brief.

Comparison

Core materials compared

EPS dominates overall volume, but PIR is common in the UK, and each foam behaves differently.

EPS

Expanded polystyrene

- Most common SIP core (dominant market share)

- Rigid bead foam laminated to skins

- Requires a glue line during lamination

PIR

Polyisocyanurate

- Common UK core option

- Strong insulation per thickness

- Often selected for improved fire performance

XPS

Extruded polystyrene

- Higher density, still styrene-based

- Less common in SIP manufacturing

- Laminated with adhesive like EPS

PU

Polyurethane (urethane)

- Foam expands and bonds to skins

- Often eliminates a separate glue line

- High insulation per thickness

Performance snapshot

SIPs deliver structural strength and thermal performance in one move. Their continuous insulation gives excellent U-values, while the composite action handles high loads with less material.

Compressive strength and bilateral loading

Think of SIPs as a composite beam. The skins resist compression and tension, while the core keeps everything aligned. Panels must be detailed for loads from both directions (wind suction and pressure), so skin selection, fasteners, and splines matter.

Available sizes and thicknesses

Sizes vary by manufacturer, but a common rhythm in the UK is 1200mm or 1220mm wide panels with lengths cut to suit the design. Thickness is chosen by structure and U-value targets. Typical ranges are 90mm to 250mm depending on walls, roofs, and floors. Always confirm spans and thicknesses with manufacturer tables.

Skin materials: OSB, metal, and cementitious

SIP skins define how panels handle weather exposure, fire, and site work. OSB is the dominant skin, but metal and cementitious skins are used where different performance priorities matter.

Comparison

Skin materials compared

Most SIPs use OSB, but metal and cement skins solve different problems.

OSB skins

Most common

- Largest market share

- Exposure-rated panels handle short wet periods

- Jumbo formats enable fewer joints

Metal skins

Narrow but long

- Laminated metal skins from coil stock

- Finished surface potential in some systems

- Often paired with urethane core (cold storage origins)

Cementitious skins

Fire and pest resistant

- Concrete-impregnated panels

- Used in harsher climates and high fire regions

- Heavier and smaller formats

Fire performance comparison

Fire behavior is about the whole assembly, not just the core. Skins behave differently under heat.

Comparison

Fire behavior by skin

Panels must be tested as assemblies, but skin choice changes how fire is managed.

OSB skins

- Combustible, but acceptable when part of a rated assembly

- Requires protective linings to meet ratings

Metal skins

- Non-combustible surface

- Can lose strength and sag under high heat

Cementitious skins

- Clear winner for non-combustible assemblies

- Often paired with urethane core for high ratings

Woodworm and insect resistance

Pests are attracted to exposed timber and cellulose, so skin choice and edge detailing matter in pest-prone climates. In the UK this is generally a low-risk consideration: woodworm is typically associated with untreated, exposed timber rather than resin-bonded OSB in a sealed SIP. It matters more for export work and warmer climates, but either way keep panels dry and edges protected until the building is weathertight.

Comparison

Pest resistance by skin

In the UK this is usually a low risk, but metal and cement skins remove timber/cellulose exposure, which reduces attraction.

OSB skins

- Resin-bonded OSB (glued strands) is generally less appealing to woodworm than untreated timber in UK conditions

- Still protect edges and keep panels dry if they’re exposed during storage or installation

Metal skins

- No timber/cellulose for woodworm to attack

- Often used in hotter, pest-prone climates

Cementitious skins

- No timber/cellulose for woodworm to attack

- Popular in southern and tropical regions

Panel size constraints

Panel size impacts joints, crane planning, and transport. Skin choice influences maximum size.

Comparison

Panel size comparison

Skin type drives the maximum panel size and transport strategy.

OSB skins

- Jumbo panels up to about 2.4 m x 7.3 m

- Fewer joints and faster enclosure

Metal skins

- Long lengths possible from coil stock

- Finished widths around 1.12 m to 1.14 m

Cementitious skins

- Smaller maximum sizes

- Typically up to about 1.2 m x 4.3 m

Weight and handling

Weight changes labor, equipment, and install speed.

Comparison

Panel weight comparison

Weight drives site handling, lifting plans, and crew size.

OSB skins

- About 13 kg per m²

- 172 mm panel (2.44 m x 1.22 m) ≈ 38 kg

Metal skins

- Often lighter than OSB panels (around 10 kg per m²)

- Easier manual handling

Cementitious skins

- Significantly heavier than OSB (around 30 kg per m²)

- 2.44 m x 1.22 m panel can approach 90 kg

Field modifications

Cutting and adjustment depends on the tools and dust control on site.

Comparison

Field modification comparison

All skins can be modified, but the effort and tooling differ.

OSB skins

- Easy to cut with standard carpentry tools

- Most crews are already comfortable with wood

Metal skins

- Modifications are feasible with metal tools

- Often a switch from nail gun to screw gun

Cementitious skins

- More dust and slower cutting

- Requires specialized blades and PPE

Finish material reality check

Skins are structural. You still need a durable exterior finish.

Comparison

Finish material suitability

Do not leave the structural skin exposed to weather.

OSB skins

- Not a finished exterior surface

- Must be protected with cladding

Metal skins

- Can be a finished surface in some systems

- Still needs detailing for longevity

Cementitious skins

- Can accept parging or stucco finishes

- Often used where a hard surface is desired

Common myths to clear up

- "SIPs are just foam with wood stuck on." They are engineered composites.

- "They are weak in fire." Fire resistance depends on the tested assembly, lining, and detailing.

- "You cannot modify them on site." You can, but you need to plan penetrations.

Lesson checklist

- Know the three SIP layers and how they share load.

- Understand why continuous insulation changes energy performance.

- Learn where SIPs are best used: floors, walls, and roofs.